Searching for the legacy of Bruno Eslava Molina – the last craftsman of Mexican relief-portraits, so-called foto-esculturas, Performing Pictures have been looking for ways to reinvoke and reappropriate this extinct art form. During November, December and January 2014, Geska and Robert Brečević were working in Oaxaca, Mexico on invitation of Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo and in collaboration with Talleres Comunitarios de Zegache in Santa Ana in Mexico. The working visit was supported by the Swedish Arts Grants Committee.

Beginning in the late 1920s (and continuing through the 1980s) artisans in Mexico began producing foto-esculturas: portraits that combine photography, sculpture and painting to produce three-dimensional likenesses. These photo-sculptures were inexpensive to produce and were often commissioned from traveling salesmen to commemorate important events (weddings, family celebrations), memorialise the dead, honour individuals, etc.

Foto-esculturas were very popular throughout Mexico and even in Mexican-American communities in the US. However, there is almost no documentation of these vernacular images, or objects, in the history of photography. In short, vernaculars are photography's parergon, the part of its history that has been pushed to the margins(or beyond them to oblivion) precisely in order to delimit what is and is not proper to this history's enterprise.

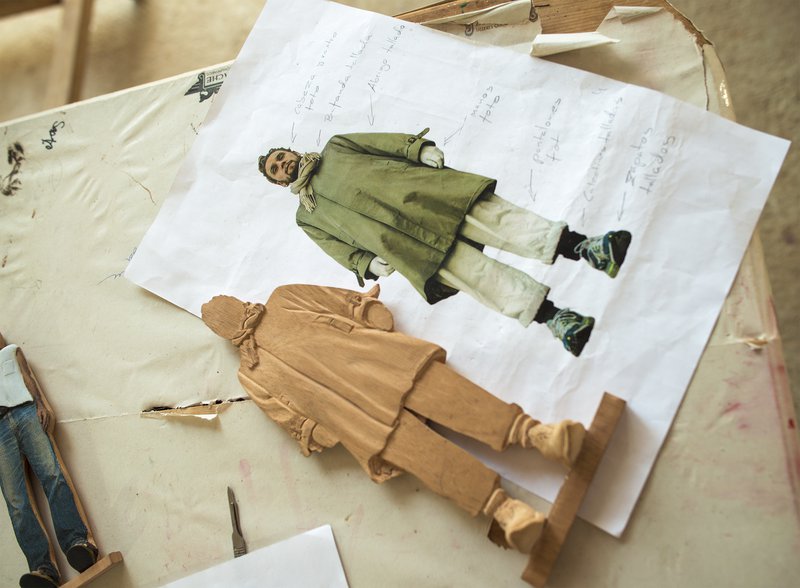

The process begins with an existing photograph, which is sent to an artisanal workshop where it is transformed into sculptural form. The artisan would copy and enlarge the photo, then cut out the face from the copied photo and mould this onto a wooden bust. Often the photo would be hand-coloured, and decoration would also be added to the bust (dimensionally or through painting) to complete the portrait – clothing, hats, accessories, etc. Finally, the portrait would be sandwiched between two sheets of bevelled glass, and generally placed in an elaborate frame.

The physical dimension of these objects lends them a distinctive quality, and for Mexican families these were often the centrepiece of homemade altars or shrines. One of the many casualties of the earthquake that hit Mexico City in 1985 was the folk art known as foto-escultura, or photo-sculpture. Before the earthquake, a small group of artisans skilled in transforming beloved photographic portraits into handmade sculptural keepsakes occupied the same building on Donceles Street in the historic centre of the city. After the earthquake destroyed the building, almost all of the practitioners closed up shop. The last crafter of foto-esculturas was Bruno Eslava Molina, whose legacy we will follow in our work.